Over the past three to four decades, demands to modernize madrasas in India have gained momentum. This article analyzes the need for modernization within the context of traditional Islamic education, socio-economic changes, contemporary challenges, and governmental initiatives. Tracing the historical evolution from medieval Muslim rulers’ educational institutions to current economic and curricular hurdles, the study highlights existing obstacles and ongoing reform efforts in this transformative process.

Main points:

- Madrasas need to teach both religious studies and skills like science or computers to help students in today’s world.

- Most madrasa students are from poor families who can’t afford regular schools. Many drop out by age 20 to work low-paying jobs.

- Efforts since the 1980s to add modern subjects faced distrust. Some states even removed madrasa recognition, causing friction.

- A few madrasas, like those linked to Dawat-e-Islami, now teach English and math, but they lack funds and trained teachers.

- Solutions need teamwork: fund madrasas, train teachers, and make their degrees valid in colleges like DU or JNU.

The modernization of madrasas in India is a multifaceted issue that has sparked debates and research for decades. Traditionally, these institutions focused on religious education, but shifting socio-economic realities have intensified calls for updating their curricula and governance.

In medieval India, Muslim rulers pioneered a unique educational vision. Quranic and Hadith studies were prioritized, but madrasas, maktabs (primary schools), and mosques also emphasized social and moral values. Rulers like Firoz Shah Tughlaq (1351–1388) and Sultan Sikandar (1489–1517) enriched this system. Later, emperors such as Akbar (1556–1605) and Aurangzeb (1658–1707) incorporated secular elements, reflecting the dynamic interplay between religious and worldly knowledge in Islamic education.

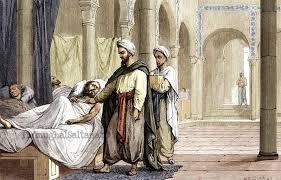

The Islamic Golden Age (8th–13th century) saw Muslim societies thrive economically, culturally, and intellectually. Scholars like Al-Khwarizmi (founder of algebra), Ibn al-Haytham (pioneer of optics), and Ibn Sina (author of The Canon of Medicine) revolutionized science, philosophy, and medicine. Centers like Baitul Hikmah (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad became hubs of multidisciplinary research, where scholars of diverse faiths translated Greek, Sanskrit, and Persian texts into Arabic, later influencing Europe. While madrasas focused on religious training, institutions like Baitul Hikmah epitomized intellectual openness and scientific rigor.

Today, India’s Muslim community faces socio-economic marginalization, with literacy rates lagging behind the national average (67.6% vs. 74.4%). Madrasas, often the only option for impoverished families, remain constrained by outdated curricula centered on Urdu, Arabic, and Quranic memorization (hifz). Limited exposure to science, mathematics, English, and technical skills hampers employability. By 2006, only 9.39% of primary-school children attended madrasas, with over 90% hailing from low-income households. Most students drop out by their early 20s due to financial pressures, migrating to cities like Kerala, Jaipur, or Jodhpur for menial jobs.

In 1986, India launched a madarsa modernization scheme to integrate science, math, and languages into traditional curricula. However, resistance from conservative factions and suspicions of governmental overreach hindered progress. A 2002 memo mandated that state-funded madrasas refrain from “anti-national activities,” further polarizing stakeholders. In 2018, PM Narendra Modi emphasized empowering Muslim youth with “Quran and computers,” though tangible outcomes remain sparse. Some states have derecognized madrasas or stripped Islamic subjects, sparking debates on cultural erasure.

Larger institutions like Darul Uloom Deoband, Al-Jamiatul Ashrafia (Azamgarh), and Nadwatul Ulama (Lucknow) now blend religious and modern education. Smaller azaad madrasas (independent madrasas), particularly in rural areas, struggle with resources. Exceptions include madrasas affiliated with Dawat-e-Islami, which have introduced English and science.

Experts argue that adding modern subjects alone is insufficient. Success requires trained teachers, updated pedagogy, funding, and community buy-in. Balancing tradition with innovation demands collaboration between governments, madrasa boards, and civil society. Overcoming regressive mindsets through dialogue and awareness is equally critical.

Modernizing India’s madrasas is a long-term endeavor requiring synergy between policymakers, educators, and communities. Historically, Islamic education harmonized spiritual and secular knowledge, a model worth reviving. Addressing economic disparities and curricular gaps can transform madrasas into holistic institutions, empowering marginalized Muslims while preserving their cultural identity. With inclusive policies and societal support, these centers can bridge tradition and modernity, ensuring relevance in a rapidly evolving world.

References

- MUSLIM EDUCATION IN INDIA: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE By Ajaz Ahmad Telwani

- https://www.biharanjuman.org/modernization_of_madarsa.htm

- https://www.hindustantimes.com/india/madrassas-hardly-matter-for-muslims/story-I9sT2Kse5f8LbAmdHqmJIK.html

- https://thediplomat.com/2017/03/indias-emerging-modern-madrasas/

- Locating the Madrasa in 21st-Century India by Ayjaz Wani and Rasheed Kidwai.

Sahil Razvi is a research scholar specialising in Sufism and Islamic History. He is an alumnus of Jamia Millia Islamia.